Government owners are the stewards of the federal/state/county/local built environment, yet many, if not most, have generally not taken responsibility for their respective roles. This includes the largest Government facilities owner/manager, the GSA, as well as other State and County Governments, etc.

Federal agencies generally do not employ a best practice of “structuring budgets to identify the funding allotted (1) for maintenance and repairs and (2) to address existing backlogs.” – GAO Report – GAO-14-188

To this day, many if not most most, Owners do not have a standardized method of deploying LEAN construction management practices across their organization. For example, the GSA doesn’t require the use of locally researched unit price detailed line item construction cost data, or the standardized used of LEAN construction delivery methods such as Job Order Contracting for all repair, renovation, and minor new construction. Common terms, definitions, and data architectures are not required, nor is BEST VALUE procurement the norm. Despite the fact that all of these core elements have proven to be needed in order to improve financial visibility and reduce rampant waste, the majority of the public sector remains mired in a profound lack of leadership.

It’sbeyond time for global oversight and taking full advantage of local support and knowledge, as all well as the implementation of collaborative LEAN construction delivery methods such as Integrated Project Delivery – IPD, and Job Order Contracting – JOC.

All federal departments and agencies must have full transparency and insight regarding “annual funding of maintenance and repairs–and the corresponding effects on their maintenance and repair backlogs.” This would “promote improved effectiveness of federal real property spending.” – GAO-14-188

Collaborative LEAN construction delivery methods drive increased productivity by enabling better decision-making, greater transparency, and ultimately optimal deployment of limited economic and environment resources.

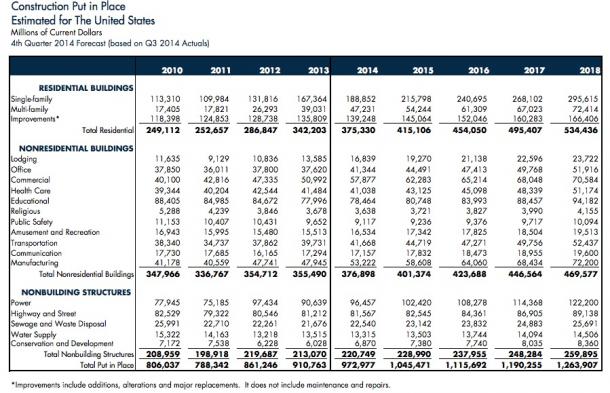

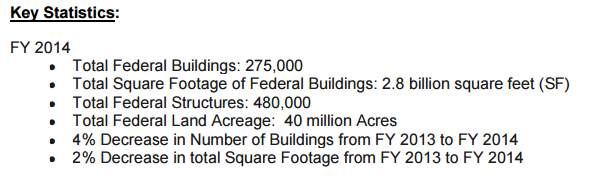

The federal government’s real property holdings are vast and diverse—comprising hundreds of thousands of buildings and permanent structures across the country, and costing billions of dollars annually to operate and maintain. Since federal real property management was placed on the High Risk List in 2003, the government has given high-level attention to this issue and has made strides in real property management, but continues to face long-standing challenges in managing its real property. For example, the federal government continues to maintain too much excess and underutilized property. It also relies too heavily on leasing in situations where ownership would be more cost efficient in the long run. In addition, the federal government faces ongoing challenges in protecting its facilities. Finally, effective real property management and reform are undermined by unreliable real property data. Specifically, despite a high level of leadership commitment to improve real property data, the federal government continues to face challenges with the accuracy and consistency of the Federal Real Property Profile (FRPP), causing the federal government to report inaccurate inventory and outcome information.

- FRPP data related to the federal government’s 480,000 structures are not reliable on a government-wide basis, due to the different approaches agencies take in defining and inventorying structures. For example, agencies use different approaches to counting structures—undermining any cross-agency comparisons.

- We found that the $3.8 billion which agencies reported in 2012 as cost savings from real property disposal, space management, sustainability, and innovation activities were not reliable

- GSA has identified $4.6 billion in maintenance and repairs expected from 2012 to 2021 and anticipates that nearly a quarter of this amount is needed immediately. However, funding for maintenance and repairs has declined since 2006. GSA officials noted that reduced funding for capital reinvestments could result in deferred maintenance and repairs, and increase the cost and extent of such work in the future. These concerns are consistent with the National Research Council’s findings that each $1 in deferred maintenance and repair work results in a long-term capital liability of $4 to $5. – GAO-12-646

- Both OMB and GAO guidance emphasize the importance of developing a long-term capital plan to guide the implementation of organizational goals. Having such a plan would enable GSA and Congress to better evaluate a range of priorities over the next 5 years. In short, more transparency through a comprehensive long-term capital plan would allow for more informed decision making by GSA and Congress among competing priorities.

– GAO 2015 Report